A little bit louder now

- James Tyler

- Apr 27, 2023

- 3 min read

Some phrases ring through history, but are they true? Did Julius Caesar ever really cry, “Et tu, Brute?” Did Alexander Graham Bell actually call out, “Watson, come here. I need you!”? Did Captain Kirk ever really order, “Beam me up, Scotty!”?

What about the famous whisper, “Eppur si muove”?

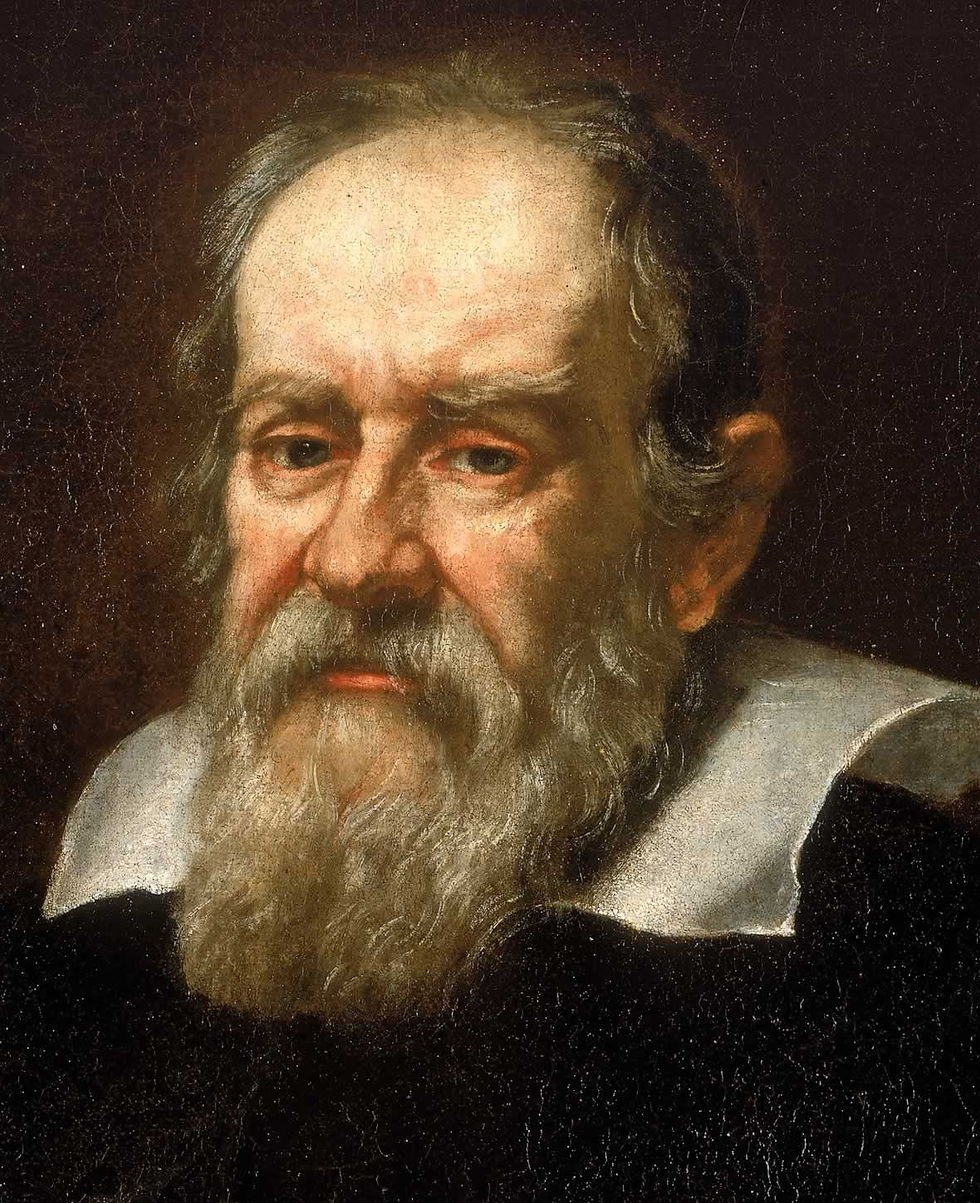

It’s 1633 in Italy and Galileo Galilei, the famous mathematician and philosopher, has been imprisoned and questioned by the Inquisition for several months.

To avoid being tortured, he has to recant his claims that the Earth is not the stationary center of the universe. He has to deny the heliocentric model of the solar system that asserts the Earth revolves around the sun like any of the other planets.

So he does recant; a statement is issued, and he is released to house arrest for the remainder of his life. But no torture, at least.

If you were facing torture by the Inquisition and got to leave instead, would you stamp your foot and declare “And yet it moves!” while still in the room with your jailors? Maybe you would just murmur “Eppur si muove” like Galileo is said to have, rather heroically, done?

I probably would have waited until I got outside at least.

“Eppur si muove” makes for a terrific, science-themed T-shirt, which you can find samples of online. It’s even the title of a science-related episode from the fifth season of the TV show “The West Wing.”

To show Galileo standing up for scientific progress by slyly muttering the famous phrase in defiance of the Inquisition seems like it would be a central scene of any drama about his life.

So why didn’t Bertolt Brecht include it in his play “Life of Galileo,” which was written in 1938 and first performed (in German) at the Zurich Schauspielhaus on Sept. 9, 1943?

I recently read Brecht’s drama about the famous scientist (an “American” version written shortly after World War II.) So it was a surprise not to find that scene in his play.

In Brecht’s “Life of Galileo,” there’s no “Eppur si muove” moment of heroic defiance. There’s not even a scene depicting Galileo having to recant. We see his students waiting to hear if St. Mark’s bell will be rung to announce his recantation. They’re hoping he holds out against the Inquisition, the Pope, the Catholic church.

Alas, there’s a lot of disappointment, resentment and denouncement when the bell does ring. Score one for the Inquisition!

Galileo did ultimately recant his book and teachings. But before you write him off as a coward … Brecht’s play ends years later, after Galileo has been kept under house arrest but allowed to still experiment and write.

His former student Andrea returns and smuggles a secret copy of “The Discourses Concerning Two New Sciences: Mechanics and Local Motion” across the Italian border to eventually get it to Holland to share it with philosophers in other nations.

Maybe there’s no scene with the famous utterance in the play, but Galileo still gets his revolutionary ideas out to the world and posterity.

But Brecht’s disillusioned Galileo has a warning for Andrea, future scientists and the world to come:

“If the scientists, brought to heal by self-interested rulers, limit themselves to piling up knowledge for knowledge’s sake, then science can be crippled and your new machines will lead to nothing but new impositions. You may in due course discover all that there is to discover, and your progress will nonetheless be nothing but progress away from mankind. The gap between you and it may one day become so wide that your cry of triumph at some new achievement will be echoed by a universal cry of horror.”

Looks like Galileo had something to say after all.

Comentarios